|

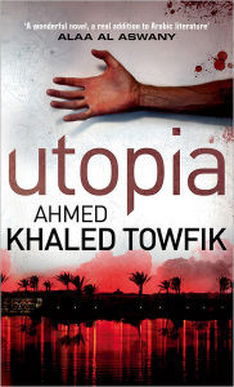

Ahmed Khaled Towfik, Utopia, Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing, 2011. Translation: Chip Rossetti. First published in 2009 in Cairo, a year before the Arab Spring begun, this near future novel has something prophetic in it. But even some 8 years after the events, Utopia is a tale of violence and social unrest that still remains topical. He gets up, takes drugs, has sex with the African maid, eats then goes to vomit on his mother's bedroom floor, goes out with his friends, has sex with them, does drugs with them. He's the scion of a wealthy pharmaceutical billionaire and he's bored. He wants to go outside and hunt an Other, kill him and bring back his arm as a trophy. The other one is an Other, named Gaber. When he gets up, he doesn't know if he'll have something to eat unless the gang he belongs to finds a dog to kill, he knows there won't be medicine for his sister who has tuberculosis and he hopes he can find a book to read. One lives within Utopia, a wealthy barricaded city, protected by Marines. The other lives just outside of Utopia. Utopia is a novel that is very reminiscent of A Clockwork Orange and "A Boy and his Dog" by Harlan Ellison. Both present, just as Utopia, a main character and narrator who is a violent teenager in a dystopian world. And like A Clockwork Orange, Ahmed Khaled Towfik's novel is very much a story of its time and place: Utopia describes a near future Egypt that collapsed because the middle class collapsed, leaving only the extremely poor and the extremely rich. It is a grim and dark social commentary on Egyptian society, made even grimer to the European 2017 reader who hasn't seen much change, sadly, after the Arab Spring. But in our current state of affairs it can also be read as universal. The two main protagonists are the alternating first person narrators: one is the predator, the other the prey, as described in the titles of the parts of the novel. Violence is not only a social violence, it is inherent to both characters, the first one because he's bored and pampered, the other because it's his only way to survive. The first one inherits the characteristics of Alex in A Clockwork Orange and of Vic in "A Boy and his Dog", making him unsympathetic and as deshumanized as those he calls the Others, the poor who live outside the gates of Utopia. Gaber feels more sympathetic, but, as he wonders himself, is it because he still has a shred of morals or is it because Utopia won and he has accepted he's the dog to his whipping master? As is often the case with such novels whose message is in the world depicted itself, Utopia has difficulties to avoid being some sort of continuous exposition. The world of the Egyptian lumpen proletariat is described at length: its filth, its despair, its hunger, its violence, and particularly its violence towards women, including rape. But though it is a striking read, it lacks a satisfying pace. The open ending is also a bit unsatisfying, leaving the reader the choice of the outcome. But, maybe, in 2009, an open ending was optimistic. In 2017, it feels as if the story lacks closure. Despite its shocking aspects, it won't feel ground breaking to any seasoned scifi reader and it can also be sometimes awkward in its storytelling. But Utopia is a striking read with a powerful social commentary that shouldn't be underestimated and that will satisfy anyone who likes political SF. If you've liked Utopia, you may also like

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

All reviews are spoiler free unless explicitly stated otherwise.

I only review stories I have liked even if my opinion may be nuanced. It doesn't apply for the "Novels published before 1978" series of blog posts. Comments are closed, having neither time nor the inclination to moderate them. |

WHAT IS THE MIDDLE SHELF?

The middle shelf is a science-fiction and fantasy books reviewS blog, bringing you diverse and great stories .

PLEASE SUPPORT AUTHORS.

IF YOU LIKE IT, BUY IT. |

ON THE MIDDLE SHELF

|

KEEP IN TOUCH WITH THE MIDDLE SHELF

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed