|

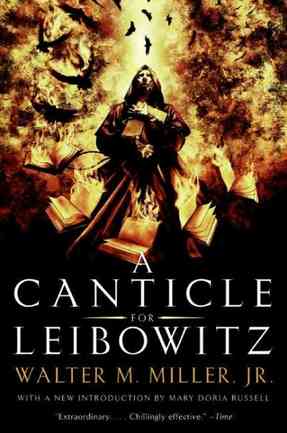

Walter Miller, A Canticle for Leibowitz, J.B. Lippincott, 1960 (original publication), SF Masterworks, 1997 (reprint). Audio version available on Audible. I couldn't remember if I had read A Canticle for Leibowitz or not. But the fact is that if I did, it was in my early teens, almost thirty years ago, so it was as good as if I hadn't. Cue my "Novels published before 1978" series, a wonderful opportunity to (re) read it. But I ended up realising that this classic scifi novel was actually highly problematic. Why am I reviewing it then? It's an interesting novel to debate and it should also be a warning to anyone being told that it's a classic to not go into it blindly. Third in my series of novels published before 1978. After a nuclear holocaust, humanity has rebelled against all knowledge. But a group of monks follow in the footsteps of a man named Leibowitz who died to preserve science. Generations later, the church of New Rome has begun a process of canonization while a novice of the order of soon-to-be Saint Leibowitz discovers more books in an abandoned nuclear shelter. Scifi has often followed trends of the latest way we have found to destroy ourselves: clifi is very much en vogue currently, nuclear holocausts were two a penny in the 1950s-1960s. So just like in the Leigh Brackett novel I reviewed recently, humanity has been decimated by a nuclear war, and science and technology are viewed with deep mistrust. That ended up being a problem: it didn't feel original, on the contrary. I wasn't only reminded of Brackett, but also of Bradbury and his Fahrenheit 451, not to mention countless others. The novel consists of three parts, separated by generations: the first one takes place roughly two centuries after the nuclear holocaust; the second some centuries later, as humans rediscover electricity; the last one even later, as humans master again nuclear power and reach to the stars. Such a time span creates some difficulties. The first one is about the image of the Roman Catholic church. My suspension of disbelief was stretched so thin I thought it would snap when I realised that a supposedly Roman Catholic church would harbour and shelter technological texts. I mean... Galileo, anyone? It is briefly addressed in the second part of the novel when a free thinker tells the monks his interpretation of the science they are rediscovering may be in contradiction with their dogma. But this free thinker character is so unsympathetic and his scientific views are actually so warped by their ignorance that the monks end up again looking like the heroes preserving knowledge when in fact, their basic misunderstanding only makes of what was once knowledge dogma again. One could argue that there is a tongue-in-cheek play with the Roman Catholic church dogmas here, since, just as it considers a Jewish man as its Messiah, it is here considering a Jewish engineer, Leibowitz, as a saint. Leibowitz would then become a Christic figure for the apocalyptic times. The third part has its share of unsympathetic characters, particularly a monk who preaches to a dying woman and son to not commit suicide even if they are suffering tremendously from being irradiated by a nuclear blast. This denial of the freedom to choose your own death, even if it is in accordance with the Roman Catholic dogma, felt incredibly violent and made the character very remote to me. Furthermore, the order of Saint Leibowitz goes from benevolent in the first, and even the second part, an order you can sympathise with, to being part of an oppressive system that forces incredible pain on people in the third part. The treatment of the Roman Catholic church within the novel itself doesn't feel exactly consistent. One could argue that A Canticle for Leibowitz spans centuries, that religions change but we end up with the paradox that it seems much more enlightened in a time of ignorance than in a time of science. It is interesting to note that Miller converted to the Catholic faith after having had to bomb an abbey in Italy during the Second World War. There's most certainly some deeper connection to dig around here. The second part is hugely problematic also because of its blatant racism against Native Americans. "Ah, come on, C.!" some of you may be thinking, "They aren't explicitly referred to as Native Americans." Yeah, right... They are nomads, with stereotypical names that seems to be out of a Western, like Mad Bear, despising other humans they don't consider as true people and perceive them as weaklings. Even if Miller didn't want to make them Native Americans, the end result is that he wrote a racist stereotype used for Native Americans in the US colonialist fictions. "Hang on, C." are you asking, "Did you find any redeeming quality in the novel?" The fact is that I'm now regretting reading the novel rather than the novella, which is only the first part of the novel. The novella has a lovely, slightly naive quality to it, all in big brushstrokes and vivid colours, carried by a simple and endearing character. The use of the Roman Catholic church even makes complete sense in it, offering characters in situations bordering on martyrdom and hermitage. The mysterious Jewish character who weaves in and out of the three parts is highly interesting and often provides a much needed humour and step back. I appreciated he remained a mystery which opens up the interpretations (Jesus? The Wandering Jew (1)?Leibowitz? Miller himself?). He also creates a very important link through all the parts. I think that my reading of it is, once again, highly influenced by the times we live in. In the 1960s, the focus of a reader would have been the disappearance of technology, the fight to preserve some knowledge, the threat of nuclear annihilation. As a reader of the early 21st century, I could only see that others had done the first two aspects in ways I found more striking and still contemporary and, in our times when religions are used by some to bolster extreme politics, the treatment of the Roman Catholic church aspect felt to me as problematic, to say nothing of the unacceptable racism. So, to read A Canticle for Leibowitz or not to read A Canticle for Leibowitz? I would say that, by all means, read the novella. It is well written, it has an endearing character, a well done if not original premise; a comparison with Brackett's Long Tomorrow would certainly provide some food for thought on the theme of chosen ignorance and fear of technology (which I actually preferred on those themes). But I think that if you're going for the novel itself, expect to argue with it violently, not because it'll take you out of your comfort zone, but because what was glossed upon by past commentators can't be glossed upon by readers nowadays. (1) Many thanks to Josh Ellis for pointing out this possibility too on Twitter. If you have liked A Canticle for Leibowitz, you may also enjoy

1 Comment

18/6/2018 03:39:03 am

Hello!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

All reviews are spoiler free unless explicitly stated otherwise.

I only review stories I have liked even if my opinion may be nuanced. It doesn't apply for the "Novels published before 1978" series of blog posts. Comments are closed, having neither time nor the inclination to moderate them. |

WHAT IS THE MIDDLE SHELF?

The middle shelf is a science-fiction and fantasy books reviewS blog, bringing you diverse and great stories .

PLEASE SUPPORT AUTHORS.

IF YOU LIKE IT, BUY IT. |

ON THE MIDDLE SHELF

|

KEEP IN TOUCH WITH THE MIDDLE SHELF

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed