|

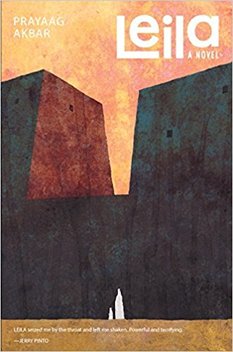

Prayaag Akbar, Leila, Simon & Schuster India, 2017. Leila is typically the kind of entirely believable dystopia that you end up being completely engrossed into. It is not a happy read but it's chilling and sadly all too easy to imagine it happening. Shalini searches for her daughter, Leila. She was taken from her sixteen years ago, when things became really bad. The walls got higher and higher ; each community lived with their own behind those walls, according to their castes, their family ties, their religion. And more and more people confined themselves within their communities, all to attain "purity". Until the day when people like Shalini, her husband Riz and their three year old daughter, living in the mixed community of the East End, became people that needed to be reeducated. What makes Leila completely chilling is how plausible it is to imagine a city partitioned by walls defining communities that live only among themselves, in contempt and fear of the others, and with their own private laws. Obviously, this hierarchical social order is very much inspired by the Indian caste system. But it's easy to transcribe it to any Western city, with its slums, its estates, its "good" or "bad" neighbouroods, its Black or White or Polish or Turkish or white collars only or working class, or whatever, areas. But here, the walls aren't metaphorical, they are literal barriers. And people go as far as asking "Should our kids breathe the same air as them?" But what makes Leila even more chilling is to see how Shalini, when she was still upper middle class and living with her husband, as liberal as she was, was treating her servants. She may not have believed in the literal walls, but she had her own metaphorical walls still firmly in place. Now that she's an outcast, she lives with being treated as a lower human being. People accept this social order, whether they are the proletariat, the lumpen proletariat or the bourgeoisie. It is the story of a moral defeat that everyone is content with and perpetuates. Shalini story is heartbreaking. Not only you read about her social fall, but you read also how the reeducation turned her into an addict to (possibly) anti-depressant pills. I was very impressed by how realistically Akbar used her appearance, in comparison to women her own age who haven't faced the hardships of reeducation, physical labour and abuse. It is such a realistic detail, that somehow, is always glossed over. Of course, the most heartbreaking aspect of her story is her grief as a mother for Leila, her lost daughter. Sixteen years and still searching, still missing her, accompanied by the ghost of her husband Riz when she celebrates her birthday by the wall of Purity One. The ending could be read as hopeful or grim. Sadly, I believe the grim ending to be much more realistic. I often find that some dystopias that try to convey a moral or social message spend too much time detailing the world building and it may be detrimental to the story. But Akbar managed to both convey the world building with some cleverly organised flashbacks that also raised the tension to the mystery of Leila's disappearance, and to have me engrossed in Shalini's story. I would argue the writing style is a bit sparse, a bit too revealing maybe of Akbar's journalistic roots. But it fits the story like a glove. Leila is an engrossing, chilling to the core and heartbreaking dystopia. It tells the universal story of the grief of a parent and how easily we reject those who are "others" to ourselves. Purity, indeed... ! Update - September 2017: Leila can be ordered via your favourite indie bookshop or you can buy it on Amazon from a seller in India. Otherwise, it will be published in the UK and Commonwealth countries via Faber & Faber in summer 2018, according to Prayaag Akbar himself. The writer's Twitter account. If you've liked Leila, you may also like

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

All reviews are spoiler free unless explicitly stated otherwise.

I only review stories I have liked even if my opinion may be nuanced. It doesn't apply for the "Novels published before 1978" series of blog posts. Comments are closed, having neither time nor the inclination to moderate them. |

WHAT IS THE MIDDLE SHELF?

The middle shelf is a science-fiction and fantasy books reviewS blog, bringing you diverse and great stories .

PLEASE SUPPORT AUTHORS.

IF YOU LIKE IT, BUY IT. |

ON THE MIDDLE SHELF

|

KEEP IN TOUCH WITH THE MIDDLE SHELF

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed